Hybrid Cloud Without Exceptions: Enforcing Governance Across Regulated Infrastructure

TLDR

- A regulated environment is one where infrastructure changes must follow documented, repeatable processes that produce consistent audit evidence across systems. In sectors such as finance, insurance, logistics, and government, failure to apply the same controls across on-prem and cloud environments often leads to audit findings and security incidents.

- IBM’s Cost of a Data Breach Report 2025 shows that organizations with fragmented security and compliance controls take an average of 241 days to identify and contain breaches, increasing regulatory and financial exposure.

- Many organizations rely on manual reviews after technical work is complete. This slows delivery but does not prevent policy violations. Enforcing compliance at the request stage allows intent to be validated before any infrastructure is modified, reducing reliance on human review.

- Compliance is not limited to initial provisioning. Without continuous oversight, temporary fixes and configuration drift accumulate over time, creating risks that are usually discovered months later during audits. Managing infrastructure as a lifecycle helps maintain approved state from creation through decommissioning.

- When governance depends on the specific technical knowledge of individual engineers, it becomes a bottleneck. Allowing developers to request outcomes instead of writing low-level infrastructure code enables consistent application of approved patterns across environments.

- Infrastructure that falls outside a governed system often leads to untracked spending and wasted energy, because ownership and purpose are lost across environment boundaries. A governing layer makes it possible to link resources to owners, business intent, and compliance requirements.

In regulated environments, audit failures often result from small, routine changes rather than major incidents. This pattern is common across highly regulated sectors such as financial services, insurance, logistics, and government-operated platforms, where infrastructure changes are subject to formal oversight. The IBM Cost of a Data Breach Report 2025 states that organizations with disconnected security and compliance controls across environments take longer to detect and contain issues, with the average breach lifecycle exceeding 292 days. That delay is rarely caused by a lack of software (it is usually caused by irregular enforcement across systems that fall under the same governance rules).

Operating across hardware and virtualized environments exposes technical differences between static ticketing and automated deployments. An on-premise firewall rule approved through a ticket, a Terraform plan run from a shared account, and a Kubernetes deployment via a pipeline can all be valid actions. Each generates different approval records, different logs, and different ownership data. During an audit, these technical differences matter more than the change itself. Auditors do not ask whether the change was correct: they ask whether the process was identical every time. This distinction sits at the core of compliance programs such as SOC 2, ISO 27001, PCI DSS, and government security standards.

Engineers in regulated sectors discuss these failures frequently. A recent thread on Reddit’s r/devops describes how audits feel like archaeology because infrastructure changes in public clouds often bypass formal change management.

Even when the technical configuration is secure, the lack of a unified record creates significant risk. Teams reported weeks of manual work to create documentation for actions that were already running in production.

Adding manual reviews is a common but ineffective response. Change requests become longer and approval chains grow more complex. Evidence is collected after the change to prove what the engineer intended. This increases wait times without fixing the underlying enforcement gap. The core issue is that hybrid infrastructure is managed as separate entities instead of a single governed environment.

This article examines hybrid environments from an operational perspective. The focus is on how governance fails across environments, why standard tools do not prevent those failures, and what regulated teams need to run hybrid infrastructure without generating exceptions.

Why Regulated and Government Environments Require Enforcement Across Hybrid Cloud

Regulated and government environments require enforcement because infrastructure changes must be provable, repeatable, and auditable across all systems involved. In hybrid cloud setups, routine changes frequently span on-prem, private cloud, and public cloud environments, each governed by different control mechanisms. Without enforcement that applies uniformly, organizations cannot demonstrate that the same policy was followed every time.

Consider a payments platform, a government service portal, or an insurance claims system where sensitive processing runs on-prem for regulatory reasons, while application services run in the public cloud. Operationally, this is one system delivering a single service. From a control perspective, it is managed through separate change processes, access models, and logging mechanisms.

The gap appears when a single logical change, such as allowing a cloud-hosted service to access regulated data on-prem, is split into multiple independent actions. Each action is approved, logged, and tracked in isolation. No system evaluates whether the combined change complies with policy as a whole, or produces a single record showing that enforcement was applied consistently end to end.

To understand why this happens, it is necessary to look at how enforcement is scoped to individual platforms, how teams compensate when no shared control exists, and how operational knowledge becomes a prerequisite for staying compliant.

Control Planes Do Not Cross Infrastructure Boundaries

In the payments platform example, an engineer needs to allow a cloud-hosted service to connect to an on-prem database. This single requirement translates into multiple technical changes. On-prem, a firewall rule must be updated through an IT change workflow with documented approval and a scheduled execution window. In the public cloud, a security group rule is modified through infrastructure tooling using cloud identity permissions. In Kubernetes, a service account or role binding is adjusted to allow the application to initiate the connection.

These actions are directly related and together, they enable one access path from a specific service to regulated data. Each system enforces its own local rules. The firewall change checks whether the rule follows network policy. The cloud platform checks whether the identity has permission to modify security groups. Kubernetes checks whether the service account is allowed to access the namespace.

The issue is that enforcement stops at these individual checks. No control evaluates the change as a whole. There is no mechanism that determines whether this specific service, running in this environment, should be allowed to access that data set under current regulatory and organizational policy. Each system approves its part without visibility into the combined outcome.

When the change is later reviewed, teams are left with separate records that describe individual actions rather than the intent they collectively served. To compensate for this gap, organizations introduce manual coordination steps to connect the dots, which increases delay and shifts enforcement from systems to people.

Manual Reviews Replace System Enforcement

When no single system enforces policy across a complete change, regulated teams compensate by adding coordination steps. These steps are not designed to enforce rules directly. They exist to reconcile actions taken across multiple platforms that were approved independently.

In the payments platform, a single access requirement spans network configuration, cloud access rules, and application permissions. Because each system evaluates only its own change, teams introduce a manual review process to connect them. Engineers are asked to submit evidence showing what was changed in each environment, such as firewall rule updates, cloud access modifications, and application permission changes, under a single request for review.

This review process attempts to answer a question no system addressed earlier: whether the combined change results in an access pattern that complies with organizational and regulatory policy. The review does not prevent the change from being prepared. It evaluates it after the technical steps are already defined, and in some cases after parts of the change are already live.

This approach introduces two structural problems of which first is review volume grows with the number of infrastructure changes, not with their risk. Routine changes require the same coordination effort as sensitive ones. Second, when a review identifies a policy misalignment or unintended access path, reversing the change is difficult. The work has already been distributed across systems with different rollback mechanisms.

Over time, this pattern reshapes how governance is experienced. Changes are perceived as slow because they wait on coordination rather than enforcement. Low-risk changes are delayed, while high-risk changes still depend on human judgment to catch issues that systems did not prevent. The process records what happened, but it does not reliably control what is allowed. From a compliance perspective, this creates a fragile state where controls exist and are documented, but they are applied after the fact and inconsistently across environments.

Infrastructure Knowledge Becomes A Compliance Gate

As manual reviews become slower and more burdensome, teams look for ways to reduce coordination overhead. In many regulated environments, this leads to governance logic being pushed into infrastructure tooling itself. Instead of relying on review boards to assess whether a change is acceptable, teams encode rules directly into how infrastructure can be defined and modified.

In the payments platform, this takes the form of constrained network templates, predefined access patterns, and platform policies enforced at the tooling level. Terraform modules limit which resources can be created, Kubernetes policies restrict which actions are allowed in certain namespaces. Network configurations enforce fixed patterns for connecting services to regulated data.

These controls reduce the need for repeated manual reviews, but they introduce a new dependency. Only engineers who understand how governance rules are expressed across all layers can make changes efficiently. Changes that fit the encoded patterns move quickly. Changes that do not require interpretation, exceptions, or specialist involvement. This again creates an uneven operating model.

Platform specialists who understand the tooling move fast because they know how to work within the constraints. Product teams wait for assistance or bypass controls through shared roles and one-off scripts to avoid delays. Compliance outcomes begin to depend on who makes the change, not on a consistently enforced system.

At this point, governance is no longer enforced primarily by shared controls. It is enforced through individual expertise. As infrastructure grows and spans more environments, this dependency on specialized knowledge becomes fragile, which pushes organizations toward architectural decisions that prioritize enforceability over flexibility.

Hybrid Cloud Architecture Under Regulatory Constraints

Hybrid cloud architecture in regulated organizations is usually shaped by external requirements rather than technical preference. Data residency rules keep databases on-prem. Latency constraints push certain services closer to users. Cost and availability considerations drive the rest into the public cloud. This architecture pattern is common in government systems and regulated industries where legacy infrastructure, national data residency rules, and long audit cycles constrain redesign options.

The result is a system that must function as one platform while running across multiple environments. The architectural challenge is not drawing the diagram. The challenge is applying the same governance expectations to every part of that diagram without forcing teams to rebuild what already exists.

Regulators Care About Consistency, Not Topology

In the payments platform, auditors do not object to workloads running in different locations. What they examine is whether access approval, change tracking, and logging follow the same rules regardless of where the workload runs.

If a database change on-prem requires approval and produces an audit trail, but a cloud service change does not, the architecture becomes harder to justify. The risk is not the hybrid design itself. The risk is that policy enforcement depends on location. This distinction matters because it shifts the focus from redesigning architecture to fixing governance coverage.

Treat Existing Infrastructure As Governable, Not Immutable

A common mistake in regulated hybrid environments is treating existing infrastructure as outside the governance system. In the payments platform, long-running on-prem databases and legacy network rules are often excluded because they were created years earlier. This creates blind spots. Ownership is unclear. Change history is incomplete. Auditors expand scope to include these systems, increasing review effort across the board.

To prevent this, existing infrastructure must be brought under governance without forcing rebuilds. Discovery, ownership attribution, and lifecycle tracking must apply retroactively, not only to new deployments. Once existing systems are governable, teams can stop debating whether to migrate and start focusing on how to manage what already runs.

Import-First Architecture Beats Rebuild-First Strategies

Rebuilding infrastructure to achieve compliance is rarely feasible in regulated industries. Migration projects require extended approval cycles, downtime planning, and budget justification. As a result, governance improvements are delayed or abandoned.

An import-first approach allows teams to start governing immediately. In the payments platform, existing on-prem databases, cloud services, and network paths are mapped into a managed system where policies, ownership, and lifecycle rules can be applied consistently. This approach aligns architecture with operational reality. Instead of waiting for a future-state platform, governance begins with the infrastructure already in production.

Some platforms address this by importing existing infrastructure into a managed model rather than requiring re-provisioning. Cycloid, for example, supports reverse-import of running cloud and on-prem resources into version-controlled infrastructure definitions. This allows teams to apply ownership, policy, and lifecycle rules to infrastructure that already exists, instead of delaying governance until a future migration.

Hybrid Cloud Management Without Exceptions

The hybrid cloud architecture described earlier defines where different parts of the system run, such as on-prem databases, public cloud services, and shared platforms. Management determines whether that system continues to meet regulatory and organizational requirements after it is deployed.

In regulated hybrid environments, compliance issues most often emerge during routine operational changes, such as updating network access rules, adjusting service permissions, scaling workloads, or modifying application configurations. These changes happen frequently and outside of initial provisioning workflows. Day two operations reveal whether governance is actively enforced or simply recorded after the fact.

In the payments platform, application services in the public cloud are updated weekly, sometimes daily. Network paths, access rules, and compute resources change as traffic patterns shift. If governance only applies at creation time, the system slowly drifts away from the approved state, even when every change was well intentioned. To prevent this, governance must move upstream into how changes are requested and downstream into how infrastructure is operated over time.

Enforce Governance At Request Time

The previous section shows why governance breaks down during routine operational changes. When access, configuration, and scaling decisions are made frequently across multiple environments, enforcing policy after the fact becomes unreliable. Request-time enforcement addresses this problem by evaluating changes before any system is modified.

In the same payments platform example, a developer needs to deploy a new version of a service that requires access to an on-prem transaction database. This requirement is not a single technical action. It translates into multiple coordinated changes: updating a network rule to allow traffic, adjusting a cloud access policy, and modifying application permissions in Kubernetes. Each platform evaluates only its own change, because approvals are scoped to that platform’s control model.

Without request-time enforcement, these actions are approved independently. The network change is valid on its own and the cloud access rule follows identity policy. The application permission is allowed within the cluster. What is never evaluated is whether this specific service, in this environment, should be allowed to access regulated data as a complete operation.

Request-time enforcement evaluates the intent behind the change before execution. Instead of approving individual actions, the system evaluates whether a service of this type is permitted to access that data class under current organizational and regulatory rules, regardless of where the underlying resources run. If the request does not comply, it is rejected before any infrastructure is modified. This replaces post-change coordination with pre-change control. Teams no longer need to explain after deployment why a combination of individually approved actions resulted in an unintended access path. They know upfront whether the request is allowed.

Once intent is enforced consistently, the next challenge becomes reducing the burden on developers by ensuring they do not need to understand every underlying system to submit compliant requests.

Separate Intent From Implementation

In many organizations, infrastructure changes are made directly through provider-specific configuration mechanisms. For cloud resources, this often means writing infrastructure definitions to create or modify services, networks, and access rules. For on-prem environments, it involves network configuration tools and change systems. For Kubernetes, it means editing manifests and role bindings that control application access.

In the payments platform, this means a developer must understand how to express the same requirement across multiple systems. To allow a service to access regulated data, they need to know how to modify cloud access rules, update network paths, and adjust application permissions. Governance relies on the engineer applying the correct pattern in each place, every time.

Here, intent and implementation are not separated.

- Intent is the policy-level requirement, for example: deploy a service that is allowed to access transaction data under defined conditions.

- Implementation is the collection of technical steps required to realize that intent, such as network rule changes, identity permissions, and application configuration updates.

Separating intent from implementation changes how governance is enforced. Developers submit requests that describe what they want to achieve, not how to configure each system. The platform evaluates whether that outcome is permitted and, if so, applies the approved infrastructure changes consistently across environments.

This separation does not remove infrastructure tooling but rather it removes the need for every requester to understand and operate it directly. Enforcement happens at the level of intent, before execution, instead of relying on individual commands to be correct.

Intent-based governance requires a structured interface that captures allowed outcomes while keeping execution standardized. Cycloid implements this by separating request inputs from infrastructure implementation, using controlled forms backed by predefined stacks. For example, a developer requests deployment of a service with approved data access and logging characteristics, while the platform applies the corresponding network, identity, and application changes using established patterns across environments.

Once intent is enforced in this way, the remaining challenge is ensuring that infrastructure continues to follow approved rules after deployment, which leads into lifecycle management.

Choose pre-defined environment variables and other specific scenarios from a simple drop-down menu.

Manage Infrastructure As A Lifecycle, Not A Deployment

Separating intent from implementation ensures that changes are approved before they are executed. However, intent-based enforcement alone is not sufficient if governance stops once infrastructure is created. In regulated and government environments, most policy violations emerge after deployment, when systems evolve through routine operational changes.

In the payments platform, services that were deployed with approved access gradually change over time. Network rules added temporarily to support troubleshooting remain in place. Service permissions are expanded to support new features and never reduced. Decommissioned services leave behind access paths that no longer serve a business purpose. Each change may be reasonable in isolation, but together they move the system away from the originally approved intent.

This is the point where governance often weakens; if enforcement applies only at creation time, there is no mechanism to ensure that the system continues to reflect approved policy as it changes. Ownership becomes unclear and evidence of why a resource exists or what it is allowed to access becomes fragmented across tools and teams.

Managing infrastructure as a lifecycle means that updates, rollbacks, and decommissioning are subject to the same controls as initial creation. Approved state is treated as something that must be preserved, not assumed. Changes are evaluated against current policy, and infrastructure that no longer serves an approved purpose can be identified and addressed.

Lifecycle enforcement requires infrastructure to remain under active management after it is deployed. Cycloid stacks persist as managed entities rather than one-time executions. This allows changes to infrastructure to be evaluated, applied, and tracked consistently over time, regardless of whether the resources run on-prem or in the public cloud.

This continuity is what allows intent-based governance to hold beyond the initial request. Without it, enforcement degrades gradually as systems evolve.

Seeing Risk Before It Becomes A Compliance Issue

Lifecycle governance depends on knowing whether infrastructure still reflects approved intent as it evolves. Without visibility into how systems connect and change over time, enforcement degrades silently. Problems are not introduced all at once. They emerge as small changes accumulate across environments.

In hybrid environments, this risk increases because relationships between services, networks, and data stores span multiple platforms. A system may still appear compliant when viewed resource by resource, while its combined behavior no longer matches policy.

Hidden Dependencies Reduce Control Confidence

In the payments platform, a cloud-hosted service reaches an on-prem database through a combination of network paths, access rules, and application permissions. Each of these elements is authorized independently by the platform it belongs to. Network controls validate routing rules. Cloud platforms validate identity permissions. Application platforms validate service access.

What is missing is visibility into the combined dependency they create. No single system shows how these individual authorizations form an end-to-end access path to regulated data. As a result, teams cannot easily verify whether a service’s access still aligns with its approved purpose.

This matters because compliance requirements are tied to what data is accessed and why it is accessed, not just how individual resources are configured. Transaction records, personal data, or government datasets are permitted to be accessed only by specific services performing defined functions. When dependencies are unclear, verifying this alignment becomes difficult.

Centralized visibility helps reduce this uncertainty. Cycloid provides a unified view of infrastructure assets and their relationships across on-prem and cloud environments, making access paths and dependencies explicit instead of inferred from tickets and logs.

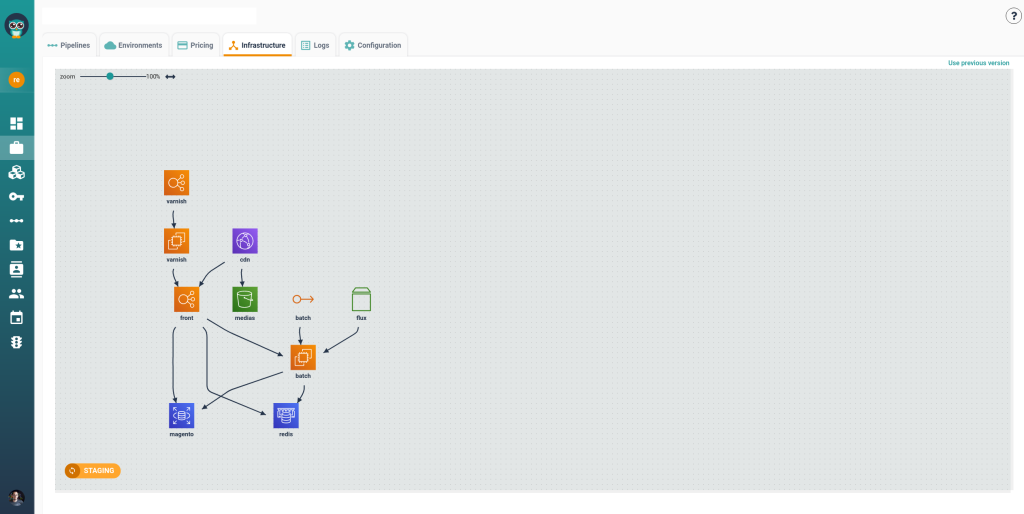

In the diagram above, each node represents a deployed component, such as a service, storage bucket, cache, or delivery layer. The arrows between them represent real, operational dependencies. For example, a front-end service routes traffic through a content delivery layer, which then connects to backend services and data stores. These relationships are not inferred from documentation. They are derived from the actual infrastructure state.

This matters because governance is rarely about a single resource. It is about who can reach what, through which intermediaries, and for what purpose. Without dependency tracking, teams evaluate permissions in isolation. With dependency tracking, they can trace a complete access path from an entry point to regulated data.

In practical terms, this allows teams to answer questions such as:

- Which services can reach this data store today?

- Through which network paths and service dependencies?

- Does each step in that path still serve an approved business function?

See up-to-date resource information from your cloud infrastructure to spread information across your team.

Why Governance Determines Cost And Energy Accountability

Cost and energy usage in regulated hybrid environments are outcomes of how infrastructure is governed over time. When systems are created without clear ownership, purpose, and lifecycle constraints, resource consumption grows independently of business need.

In practical terms, creating infrastructure allocates real capacity. Spinning up a Kubernetes cluster reserves compute, storage, and network resources. Deploying it in a specific region fixes both its cost profile and energy characteristics. If that cluster’s purpose, owner, or expected lifetime is not governed, there is no trigger to reassess whether it should still exist or operate at its current scale. This is why cost and energy issues rarely start as budgeting problems but they start when governance stops at deployment.

Cost and carbon issues in regulated hybrid environments rarely start as budgeting problems. They start as governance gaps. When infrastructure is created, modified, or left running outside a governed system, spending and energy use become difficult to explain and harder to control. In logistics and transportation platforms, where infrastructure scales with seasonal demand and geographic expansion, these governance gaps often surface first as unexplained cost growth rather than security findings. Increasingly, financial regulators and government bodies expect cost, energy usage, and ownership data to be auditable, not inferred.

Loss Of Ownership Leads To Persistent Over-Allocation

In the payments platform, most infrastructure is justified when it is created. Problems appear later when services evolve and ownership becomes unclear. Clusters created for specific workloads continue running long after their original purpose has changed. Test and staging environments are duplicated and never retired. Services retain resource allocations sized for peak usage that no longer applies.

Because these resources span on-prem and cloud environments, no single system tracks them as part of a unified lifecycle. Usage data exists, but it is detached from intent. Teams can see consumption, but they cannot easily answer why the resource still exists or who is responsible for it.

The same pattern applies to on-prem environments. Legacy workloads continue running with outdated capacity allocations because no governed process exists to reassess them. Energy usage increases not because systems are inefficient, but because nothing enforces periodic alignment with actual need.

Governance Enables Meaningful Cost And Energy Decisions

Reducing cost or energy usage requires more than visibility into consumption. It requires understanding ownership, purpose, and lifecycle state. Without that context, optimization efforts stall because teams cannot safely change or retire resources.

Governance-backed cost analysis depends on knowing who owns what and why it exists. Cycloid correlates infrastructure resources with cost and usage data across environments, allowing teams to review spend and energy usage in the context of ownership and lifecycle state.

Why Existing Tools Cannot Enforce Governance Across Hybrid Environments

Most organizations already use several tools to manage hybrid environments. Portals provide visibility, pipeline systems execute changes and each tool solves a local problem well. The failure appears when teams expect these tools to enforce governance across the full infrastructure lifecycle.

Portals Without Enforcement Increase Surface Area

Many teams deploy internal portals to centralize access to infrastructure workflows. In the payments platform, the portal links to cloud consoles, pipeline dashboards, and documentation. This improves discoverability but does not enforce policy.

When enforcement lives outside the portal, teams still rely on discipline and manual checks. Plugins and scripts are added to close gaps. Over time, the portal becomes another surface that must be maintained and audited. Visibility without control does not reduce risk. It increases the number of places where governance must be explained.

This is where the distinction between a framework and a managed platform matters. Cycloid

combines a service catalog with enforced workflows, infrastructure lifecycle management, and asset visibility. Governance is applied by the system itself, not assembled from plugins and scripts.

Pipeline Tools Execute Changes, Not Governance

Pipeline systems are effective at running workflows reliably. In the payments platform, they apply infrastructure changes, deploy services, and roll out configuration updates. What they do not do is decide whether a change should exist in the first place.

Pipelines execute what they are given; if a change violates policy, the pipeline will still run unless external enforcement blocks it. Approval steps inside pipelines often become manual gates, recreating the same review problems seen elsewhere. Execution tools are necessary, but they are not a governance system. Treating them as one shifts responsibility onto reviewers instead of controls. This leaves regulated teams with many tools and no consistent way to enforce rules across environments.

Conclusion

Hybrid cloud does not fail regulated organizations because it is complex, but it mostly does because governance is applied unevenly across environments that are expected to behave as one system. Each unmanaged path, whether a ticket-based firewall change or a direct cloud update, creates a gap that surfaces later during audits, incident reviews, or financial investigations.

The recurring pattern is consistent and controls exist, but they are scoped to individual platforms. Reviews are added to compensate, slowing delivery without preventing mistakes. Infrastructure knowledge becomes a prerequisite for compliance, turning governance into an individual responsibility instead of an organizational one.

Running a hybrid cloud without exceptions requires governance to move upstream and persist downstream. This shift is required to meet modern compliance expectations, not only to pass audits but to sustain them over time. Policies must be enforced before infrastructure is created and remain enforced as that infrastructure changes over time. Existing systems must be brought under control without requiring rebuilds. Visibility must explain how systems connect, not just what resources exist.

When governance is enforced consistently across architecture and operations, hybrid cloud stops being a source of audit risk and operational friction. It becomes a predictable operating model where compliance, delivery, and accountability can coexist without manual overhead.

FAQs

1. Does Hybrid Cloud Increase Compliance Risk?

Yes, when governance is applied differently across environments. The risk does not come from running workloads in multiple locations. It comes from inconsistent enforcement, approval paths, and audit evidence.

2. Is Hybrid Cloud Architecture Or Management More Important For Compliance?

Management determines compliance outcomes over time. Architecture defines where systems run. Governance failures usually appear during routine changes, not during initial design.

3. Can Regulated Teams Avoid Low-Level Infrastructure Tools Entirely?

No. Low-level tools remain necessary for execution. The issue is exposing those tools directly to every requester. Governance improves when intent is captured at a higher level and enforced consistently before execution.

4. Is Self-Service Compatible With Strict Governance?

Yes, when self-service is constrained and enforced instead of reviewed manually. Requests should be evaluated against policy before changes are applied, regardless of environment.