TL;DR

- Governance fails not because teams ignore rules, but because the “review model” scales linearly with headcount. If every new service requires a human to check a config, your platform team is mathematically destined to become the bottleneck.

- Eliminate subjective decisions by moving rules out of wikis and into bounded inputs, where identical requests always produce identical outcomes through StackForms.

- Stop treating self-service as a form submission problem. Shift to Governance-Wrapped Self-Service where the platform validates intent at request time and blocks invalid changes before they exist.

- Make GreenOps operational by attaching budget ceilings and cost boundaries to every environment, preventing over-provisioned resources instead of reporting on them after spend occurs.

- Extend governance beyond provisioning. Apply the same enforced paths to Day Two operations such as scaling, updating, and decommissioning so lifecycle changes do not fall back into tickets.

Introduction

A platform team supporting more than one hundred engineers rarely struggles because of missing tools such as Terraform, CI systems, or cloud consoles; it struggles because governance still depends on human review instead of platform-enforced constraints. The pressure comes from governance work that scales linearly with usage. For a data team, this usually looks like every new pipeline or warehouse environment triggering the same sequence of checks: a platform engineer reviewing Terraform for network placement, a security review for data access paths, and a finance check to confirm warehouse size and query limits, all handled by the same small set of reviewers each time.

Industry data reflects this imbalance, but the real story is in the trenches. If you look at where engineers actually vent, the pattern is identical.

In r/devops, a recent thread on “Why is DevOps still such a fragmented, exhausting mess in 2025?” details exactly this burnout. Teams are drowning in a “never-ending toolchain puzzle” where automation exists, but fragile pipelines and manual debugging still consume all available capacity.

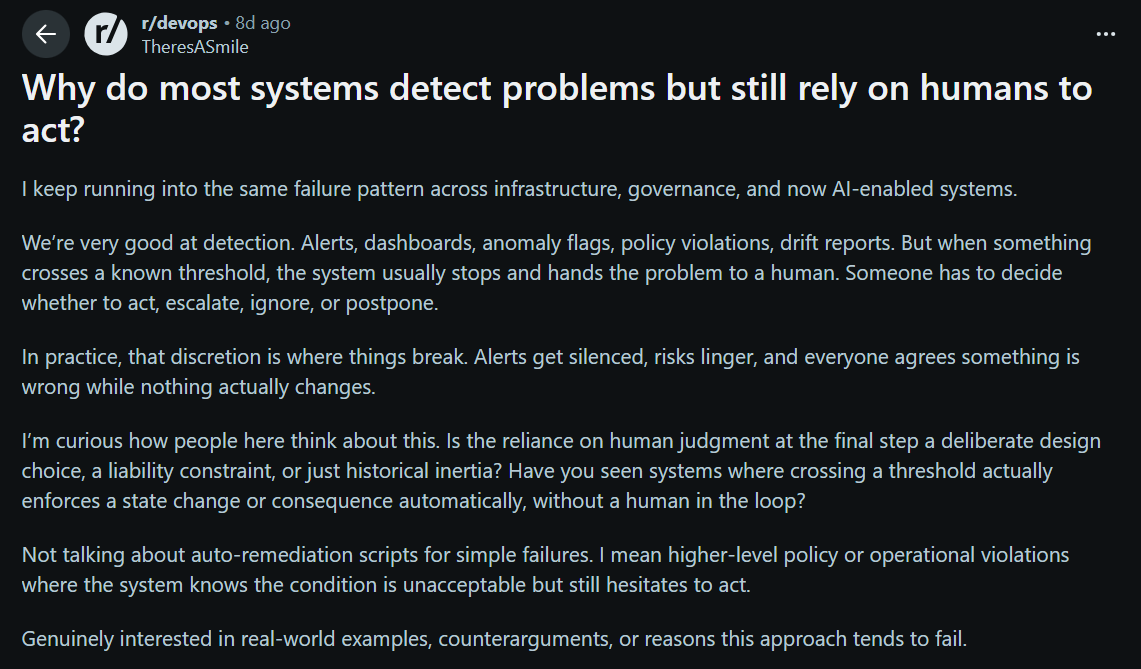

The bottleneck isn’t technical; it’s structural. Another discussion, “Why do most systems detect problems but still rely on humans to act?”, exposes the absurdity of modern governance: we have tools that flag drift or cost spikes, but we still force a human to decide whether to act.

This “human router” model is unsustainable. As noted in “Is DevOps getting harder, or are we just drowning?”, every deployment now touches five separate systems, creating maintenance overhead that grows quietly in the background until the platform team is paralyzed.

Governance is not failing because teams ignore it. It fails because enforcement depends on people being available. This article examines platform engineering initiatives that move governance into the platform itself, allowing organizations to scale control, cost boundaries, and compliance without scaling headcount.

Why Governance Becomes a Headcount Problem?

Governance becomes a staffing problem when enforcement depends on people rather than systems. Throughout 2025, platform teams confronted this at scale: growth in services, multi-cloud footprint, and transient environments drove volume well beyond what review-based models could absorb. By year’s end, a clear pattern emerged across organizations still relying on manual gates: platform teams spent more time chasing approvals than shaping platform behavior. This was not tooling deficiency, it was structural overload.

As 2026 approaches, the trend is accelerating. Gartner and industry observers expect that by 2026, roughly 80% of large software engineering organizations will have established dedicated platform teams precisely because complexity has outpaced human coordination. This suggests that governance models requiring human judgment on every change will be increasingly untenable.

This structural failure manifests in three specific ways:

1. Implicit Rules and Interpretive Drift

Security, networking, and cost rules are rarely enforced where they are written. In most organizations, they live across stale Wiki pages, scattered PRDs, and the institutional memory of a few senior engineers. None of these sources are authoritative at request time.

As a result, enforcement depends on who reviews the change and what context they have in that moment. Two identical infrastructure requests can receive different outcomes based on which document was referenced, which PRD was remembered, or which engineer happened to be on review. What looks like flexibility early on turns into inconsistency at scale.

This forces platform engineers into interpretive work. Time is spent reconciling documents, explaining boundaries, and resolving disagreements instead of encoding rules into the platform. As request volume increases, this drift compounds and governance outcomes become unpredictable by default.

2. The “Approval” Bottleneck

When a platform cannot validate intent on its own, every change is routed through a human gate. In large enterprises, this usually materializes as a ServiceNow change request or a formal change management workflow, even for routine actions such as adding an environment, resizing a cluster, or provisioning a standard database.

What begins as risk control quickly turns into queue management. Platform engineers review configurations not because the change is novel or unsafe, but because the process requires a human sign-off. Changes wait for CAB windows, reviewer availability, or compliance checklists that were never designed for high-frequency infrastructure updates.

These workflows scale poorly because the platform lacks the ability to say “no” automatically. Requests sit in queues not due to actual risk, but because no system exists to validate them against policy at submission time. In practice, this turns change management tools into traffic controllers for routine work, and platform teams into permanent approvers for decisions the platform should already know how to make.

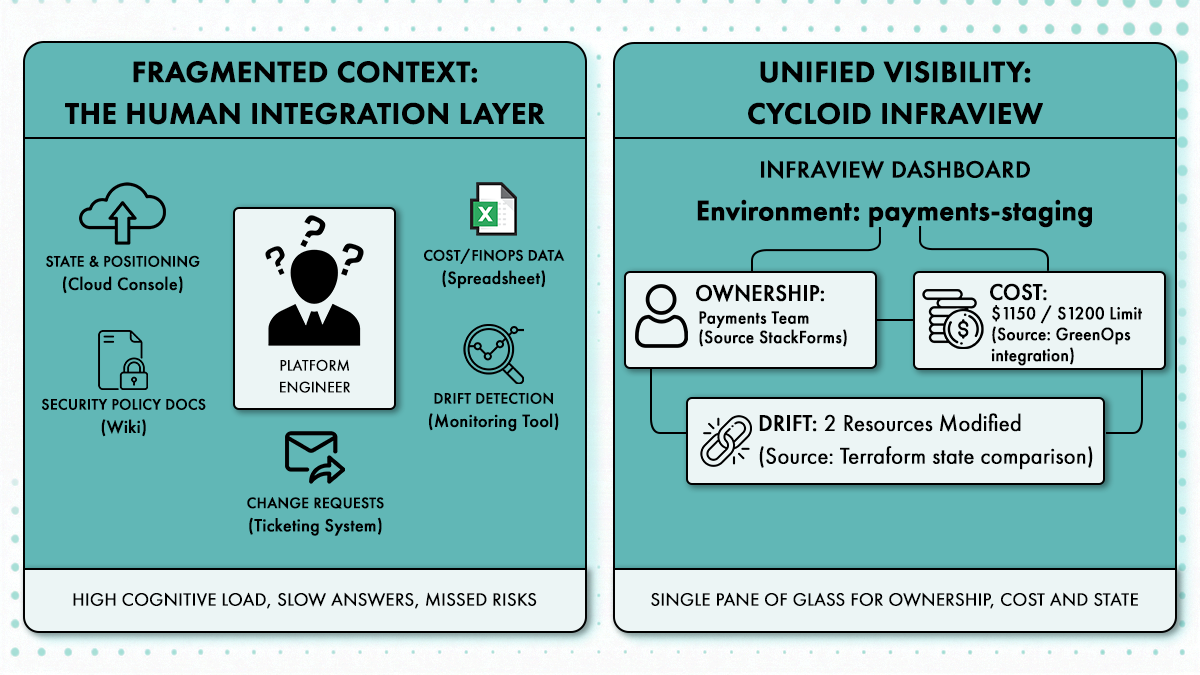

3. Fragmented Context

Infrastructure state, cost data, and security context typically live in separate systems. One tool knows what was provisioned, another tracks spend, and a third manages access. Because no single system can evaluate the end-to-end impact of a change, humans are forced to act as the integration layer. Platform engineers absorb the cost of context switching, coordinating across tools to answer simple questions like “Can we afford this?” or “Is this secure?”

What “Scaling Governance” Actually Means for Platform Teams

Consider a data platform team supporting analytics workloads across multiple product teams.

Before: governance that does not scale

A new analytics service needs a staging environment. The data team submits a request with Terraform changes. A platform engineer reviews it to check which cloud region is used, whether the warehouse size is acceptable, and if the network path allows access to production data.

Security verifies that access roles match policy. Finance checks whether the requested warehouse size fits within the team’s monthly budget. The change moves through a ServiceNow workflow because it touches shared infrastructure. None of these checks are controversial. They are also not exceptional. The same questions are asked for every new analytics environment.

As request volume grows, the platform team becomes the bottleneck. Not because the work is complex, but because governance exists only as review. Every new service increases queue length. Adding more reviewers only shifts the bottleneck. This is governance that does not scale.

After: governance that scales

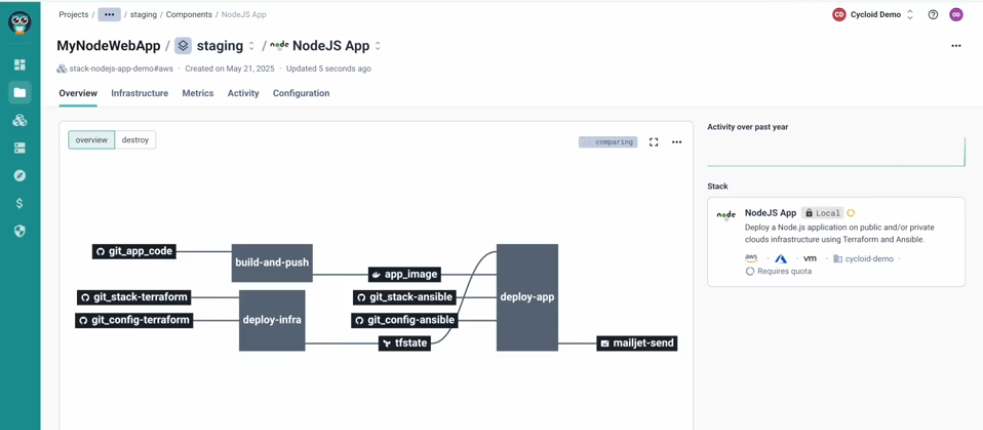

The same platform team encodes its rules into the platform.

Analytics environments are created through a governed stack. Region choices are restricted to approved locations. Warehouse sizes are capped per environment type. Network access is fixed by default. A monthly cost limit is attached to the environment.

When a data team requests a new environment, they select the analytics stack and provide a small set of inputs. If the request exceeds allowed limits, it is rejected immediately. No ServiceNow ticket is created. No reviewer is involved.

Security and finance are no longer part of the request path because their constraints are already enforced. The platform team does not approve individual environments. They maintain the rules that define them. As usage increases, governance cost stays flat. The platform absorbs the load. That is what scaling governance means in practice.

Core Platform Engineering Initiatives That Remove Manual Governance Work

Scaling governance requires deliberate platform initiatives, not incremental process changes. Each initiative below represents a program platform teams actually run to remove recurring manual work.

Initiative 1: Make guardrails the default, not an exception

Guardrails only reduce workload when they are enforced by the system, not checked by reviewers. In practice, this means policy engines evaluating requests before infrastructure is created. A common implementation is using Open Policy Agent (OPA) with Rego policies wired into the platform’s request path. When an engineer submits a request to create an environment or service, the platform evaluates that request against policy, not against a human checklist.

For example, region governance is enforced explicitly, not implied:

- A Rego policy allows production workloads only in approved regions.

- Any request targeting an unapproved region is rejected immediately.

- No Terraform plan is generated. No ticket is open.

The same applies to infrastructure shape. Instance types, node sizes, or database classes are constrained by policy. If a team requests a warehouse size outside the allowed range for that environment, the platform blocks it before provisioning. This removes the need for reviewers to manually scan Terraform diffs looking for oversized resources.

Network guardrails work the same way. Instead of reviewing security groups or VPC routing after the fact, the platform enforces fixed network tiers. A service marked as internal cannot expose a public endpoint because the policy engine rejects any request that attempts it. The engineer cannot “accidentally” violate the rule because the option does not exist.

Tagging and ownership enforcement are also handled at request time. Policies require cost center, owner team, and environment classification as mandatory inputs. Requests without ownership metadata are rejected automatically. Finance does not chase tags after deployment because untagged resources never get created.

Authentication and authorization are part of this guardrail layer. Access to create or modify environments is scoped by identity. A data team can provision analytics stacks but cannot request production application stacks. This is enforced through platform authorization, not convention.

When guardrails are enforced this way, conversations disappear. Engineers do not ask what is allowed because the platform makes it explicit. Platform teams do not review basic compliance because the system enforces it deterministically. Violations are blocked immediately, without tickets, without reviewers, and without interpretation.

Initiative 2: Replace free-form infrastructure with bounded inputs

Free-form infrastructure is what most platform teams start with. A shared Terraform repository exposes dozens of variables: region, instance size, network IDs, feature flags, resource counts, and optional modules. Teams are trusted to “use it correctly” and platform engineers review every change to make sure they did.

In this model, every variable is a potential policy violation. A team can select an unapproved region, attach the wrong network, oversize a database, or skip ownership tags. Nothing stops the request from being submitted. Governance happens later, during review. That is why every change requires inspection.

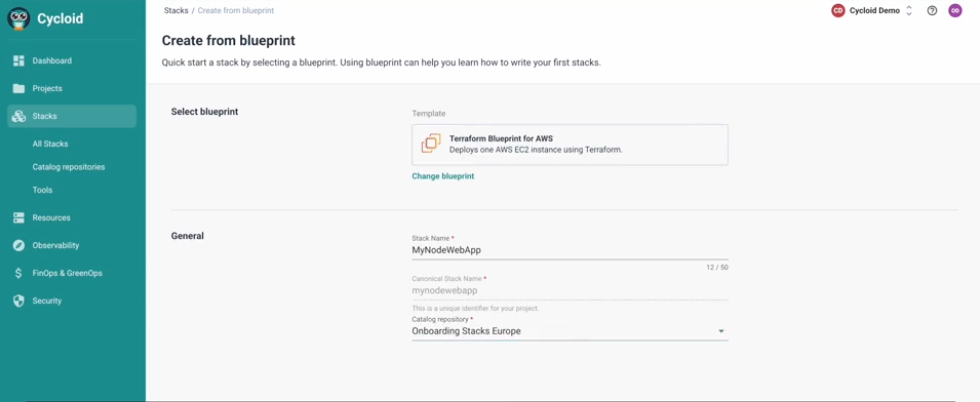

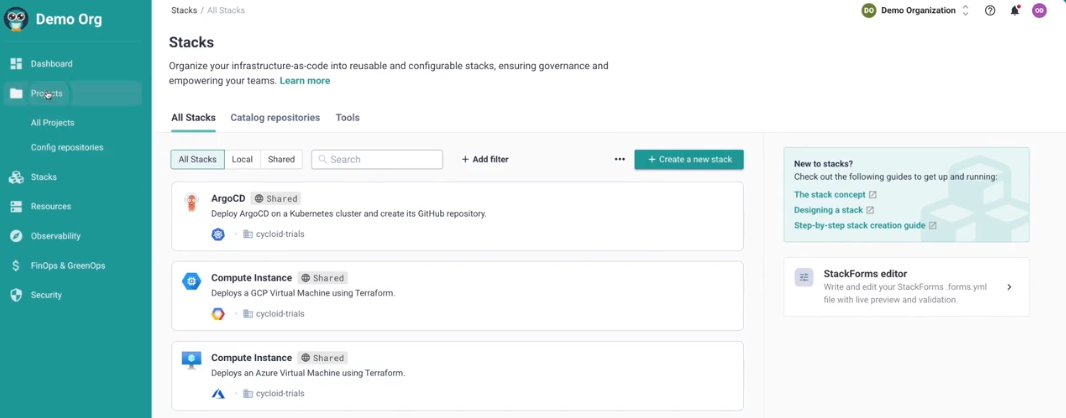

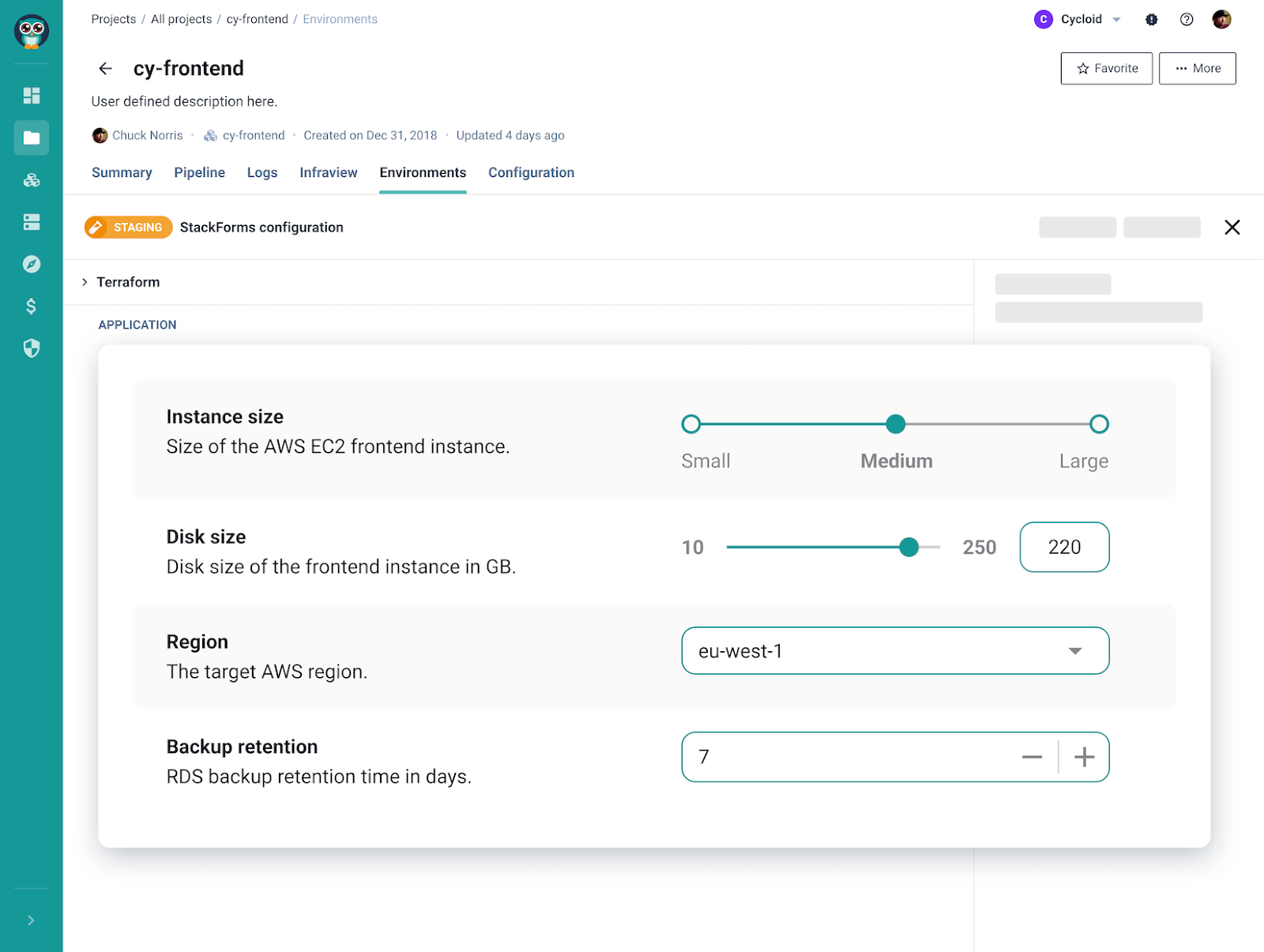

Bounded inputs invert this model. Instead of exposing everything Terraform can do, the platform exposes only what teams are allowed to change. The rest is fixed by the platform. This is where StackForms come in.

StackForms are YAML-first stack definitions backed by Terraform, not raw Terraform modules and not just UI forms. A StackForm defines:

- which Terraform stack is used

- which inputs are exposed

- the allowed values for those inputs

- which values are fixed and cannot be changed

Engineers do not edit Terraform directly. They interact with a StackForm, either through a UI or by submitting a YAML request.

A typical StackForm exposes inputs like:

- environment type (dev, staging, prod)

- service size (small, medium, large)

- region (restricted to an allowlist)

It does not expose:

- VPC IDs

- subnet mappings

- IAM role wiring

- tagging schemes

- module composition

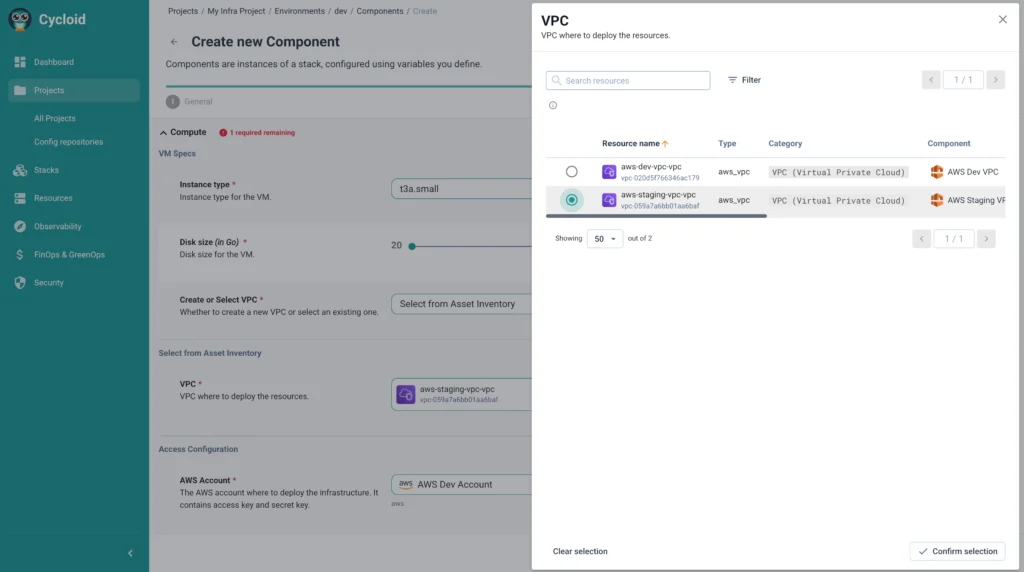

Those are locked into the stack. For example, a data team provisioning a warehouse does not choose the instance class freely. They choose from a small, approved size set. They cannot attach it to an external network because that option is not available. They cannot skip cost attribution because ownership is mandatory.

Under the hood, Terraform still runs. But the shape of what Terraform can produce is constrained before execution. This removes entire classes of review. Platform engineers no longer scan plans to check whether a team picked the wrong module, network, or resource type. Those choices are not exposed. Review work disappears because the platform cannot produce invalid configurations.

Initiative 3: Centralize visibility before enforcing control

Enforcement without visibility creates resistance. Engineers push back when they do not understand why a rule exists or what impact it has. Platform teams avoid this by exposing ownership, drift, and cost context before tightening constraints.

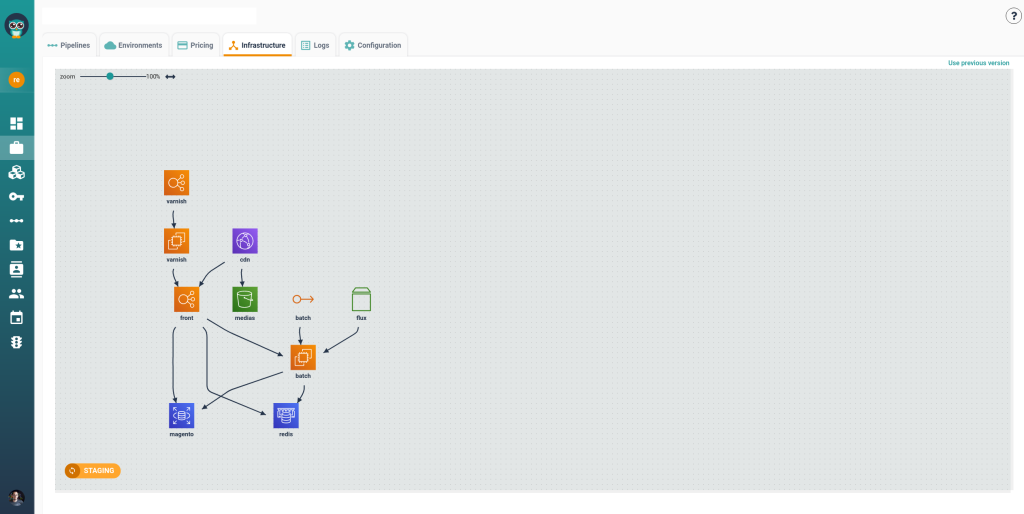

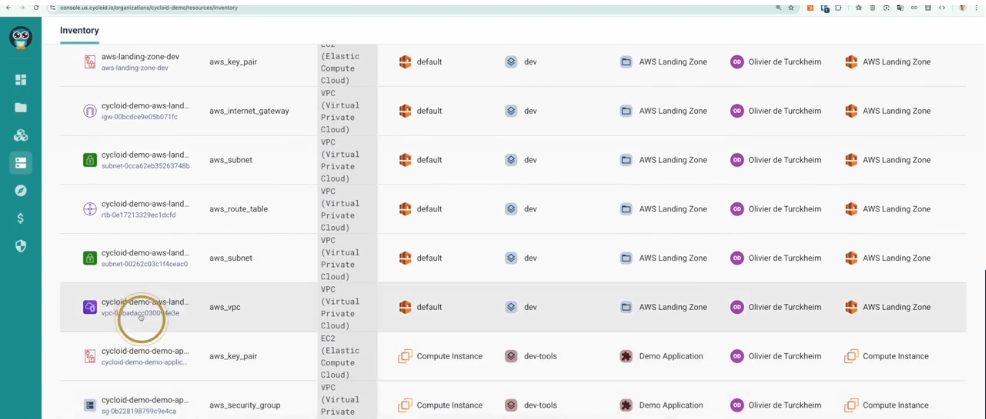

InfraView makes invisible platform state visible. Teams can see who owns what, where drift exists, and how changes affect cost. This shared context reduces friction because enforcement no longer feels arbitrary. When limits are applied, they match what teams already observe.

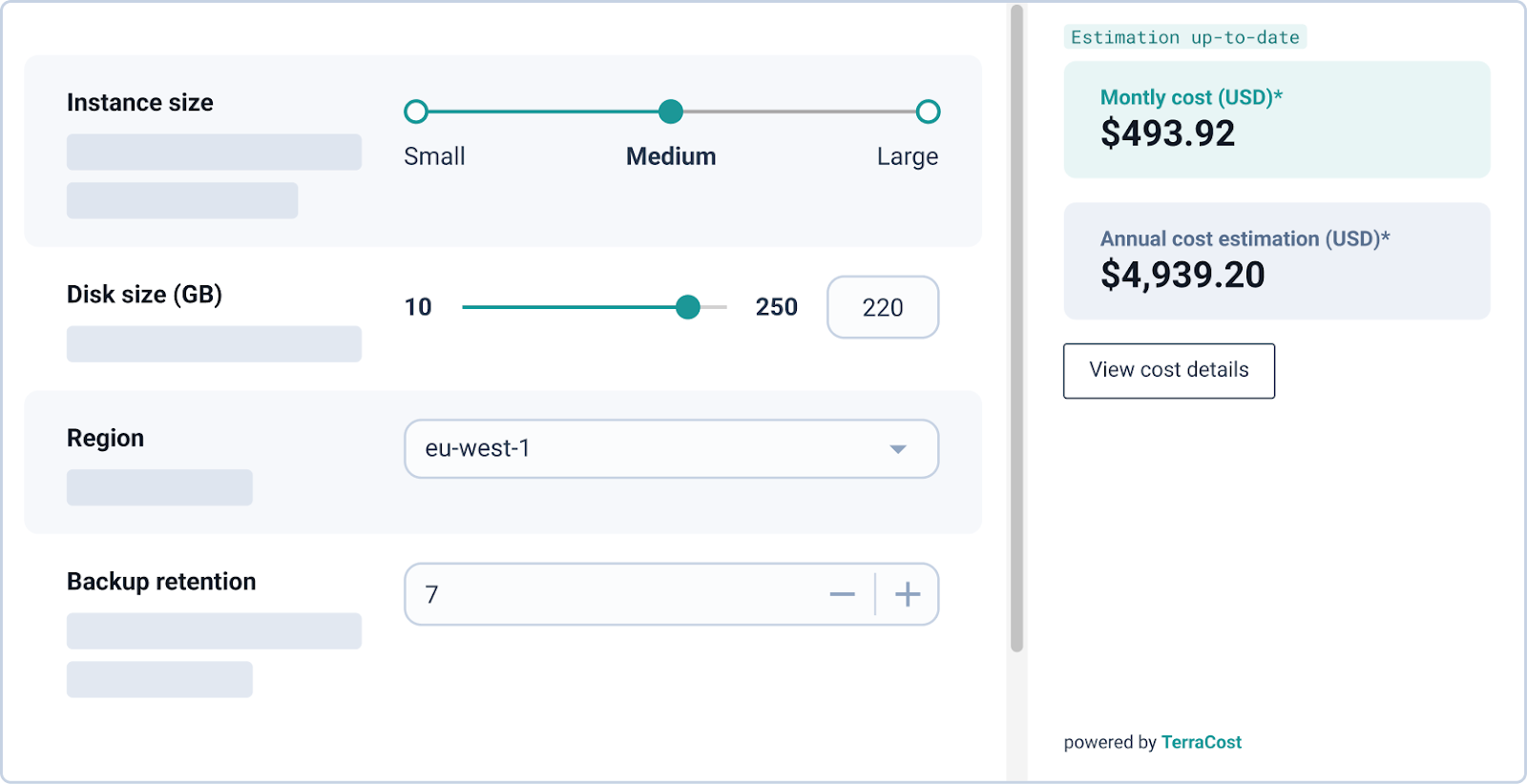

Initiative 4: Encode cost boundaries into every environment

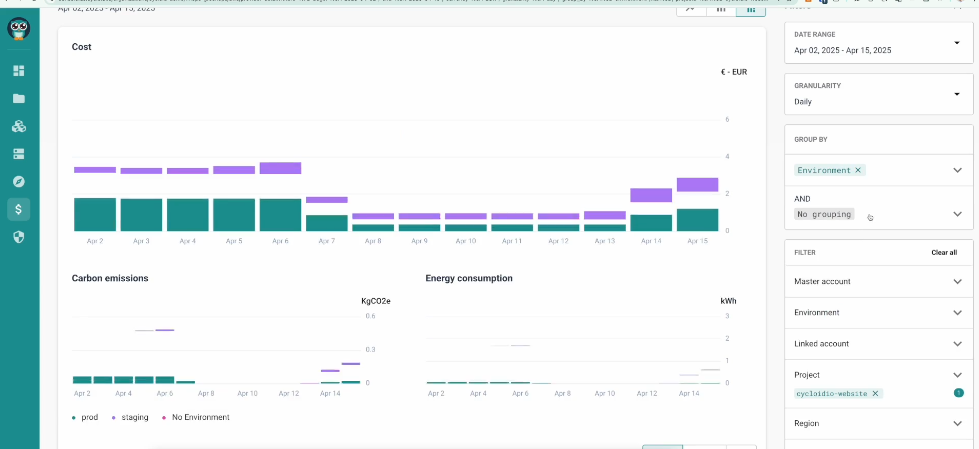

Cost governance fails when it depends on periodic reviews or finance approvals. By the time spend is flagged, the resources already exist. Cycloid remove this failure mode by encoding budgets, quotas, and limits directly into stacks and environments.

Each environment carries an explicit cost boundary. Requests that exceed it are rejected immediately. This removes finance from routine change paths while still enforcing financial control. Platform teams stop acting as intermediaries between engineering and finance.

Initiative 5: Treat Day 2 operations as a platform concern

Many platforms enforce governance during provisioning and then stop. Scaling, updates, and decommissioning fall back to tickets and manual checks. This reintroduces governance load precisely where most changes occur.

Platform teams close this gap by applying the same governed paths to Day Two operations. Updates follow defined workflows. Scaling respects predefined limits. Decommissioning enforces ownership and cleanup rules. Governance remains consistent across the full lifecycle, not just at creation time. When Day Two operations are treated as first-class platform actions, governance stays enforced without adding new review loops.

Governance-Wrapped Self-Service in Practice

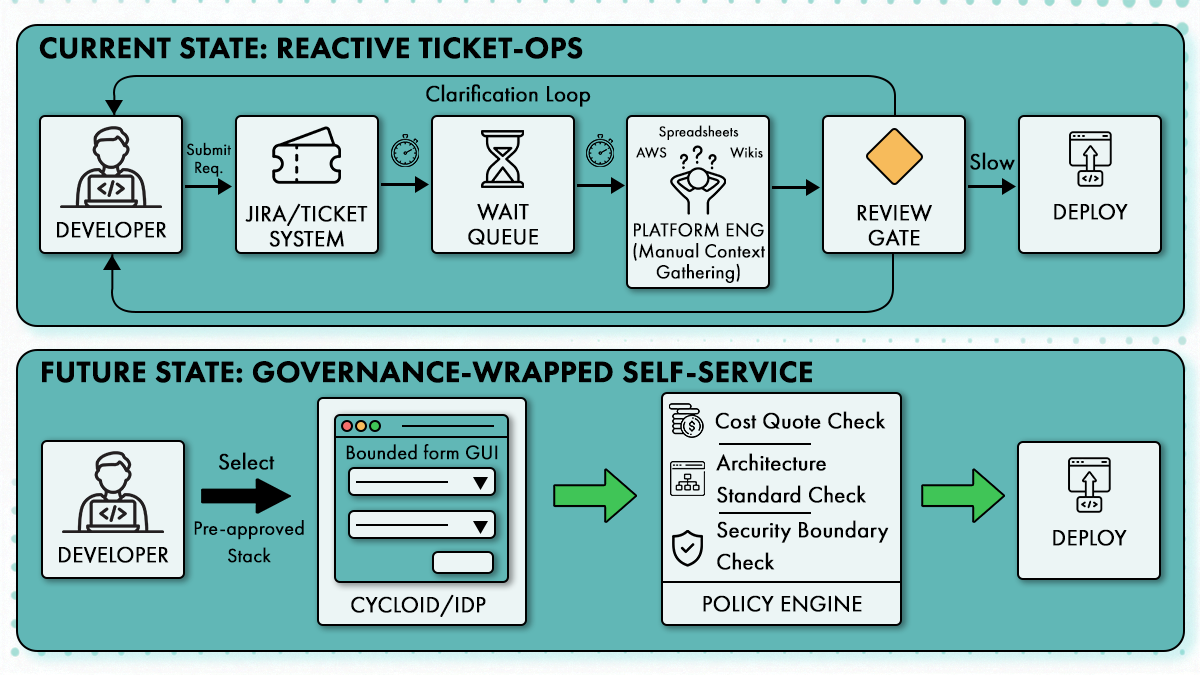

The difference between ticket-driven governance and platform-enforced self-service is not speed alone. It is where decisions are made and who makes them.

In a typical manual workflow, an engineer submits a request describing what they want to deploy. A platform engineer reviews the configuration to check architecture choices. Security verifies policy alignment. Finance flags potential cost exposure. Each step introduces delay, context loss, and subjective interpretation. The back-and-forth continues until someone signs off, often without full visibility into runtime impact.

Governed self-service changes the order of operations. The engineer does not start with a blank request. They select a predefined stack that already encodes approved architecture, network boundaries, and cost limits. Inputs are constrained to what the team is allowed to change. Policies are evaluated immediately when the request is submitted. If a request violates a rule, it is rejected on the spot.

StackForms are the mechanism that makes this workable. They hide the underlying infrastructure complexity while exposing only sanctioned inputs. Engineers focus on intent rather than implementation details. Platform teams focus on defining boundaries once rather than reviewing every change.

InfraView complements this by exposing ownership, drift, and cost impact across environments without granting console access. Teams can see what exists, who owns it, and how it behaves over time. Governance is no longer an opaque gate. It becomes visible, predictable, and enforced by the platform itself.

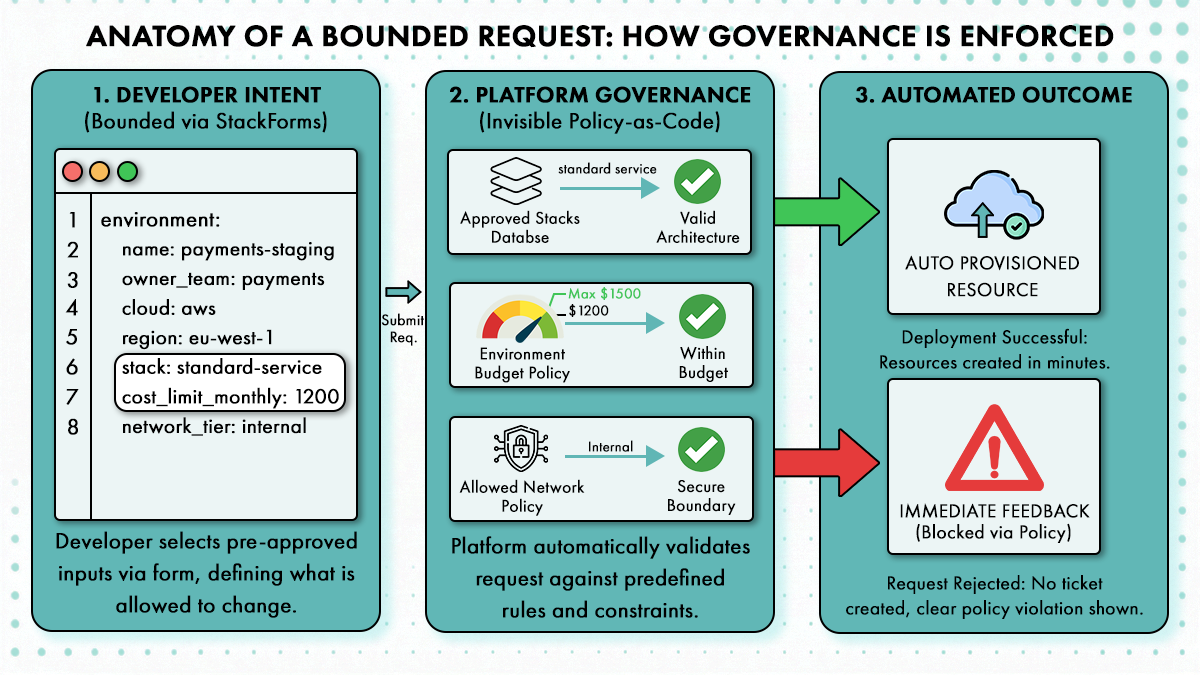

Example of a Governed Platform Request

In a governed platform, governance is embedded directly into the request, not applied later through review.

File: platform-environment.yaml

| environment: name: payments-staging owner_team: payments cloud: aws region: eu-west-1 stack: standard-service cost_limit_monthly: 1200 network_tier: internal |

The line stack: standard-service is doing the heavy lifting here. It points to a rigid definition of compute, logging, and IAM roles that the user cannot modify. They get a service; they don’t get to design the architecture.

This request does not ask for permission. It declares intent within predefined boundaries. The platform evaluates the request before any resources are created.

Region selection is validated against approved locations. The stack reference ensures only sanctioned architecture is used. Network tier selection enforces access boundaries by default. The cost limit establishes a hard ceiling for spending. Ownership is assigned at creation, not inferred later.

Because these rules are encoded into the platform, no approvals are required. The platform already knows what is allowed and blocks what is not. Platform engineers are removed from the critical path, without losing control or visibility.

Measuring Governance Success Without Counting Tickets

Platform teams often default to ticket volume as a measure of success. Fewer tickets are assumed to mean less friction. In practice, this metric hides more than it reveals.

Why ticket volume fails as a governance metric

Ticket count reflects behavior, not effectiveness. Engineers stop filing tickets when they expect long delays or inconsistent outcomes. They work around the platform, not with it. A declining ticket queue can coexist with growing drift, uncontrolled spend, and untracked exceptions. Governance success is not the absence of requests. It is the absence of human involvement in routine decisions.

Change lead time as a governance signal

Average change lead time exposes whether governance is enforced by the platform or by people. When governance is embedded, standard changes move from request to deployment without waiting on reviews. Lead time shrinks because the platform validates intent immediately. When lead time remains high for routine changes, governance is still sitting in approval queues, regardless of tooling.

Manual reviews per deployment

This metric shows how often the platform fails to decide on its own. Each manual review represents missing context, missing constraints, or missing defaults. As governed self-service matures, manual reviews should disappear for standard stacks and environments. Manual review should signal exception handling, not normal operation.

Policy violations blocked before deployment

Blocking violations after deployment shifts work downstream. Platform teams then spend time on rollback, remediation, and explanation. Violations blocked before deployment remove that work entirely. This metric shows whether governance is preventative or corrective. Only the former scales.

Cost variance and service onboarding time

Cloud spend variance by team reveals whether cost boundaries are enforced consistently. Stable variance indicates limits are applied automatically, not negotiated manually. Time to onboard a new service shows whether governance speeds up delivery or quietly slows it. When onboarding still requires tickets and approvals, governance has not moved into the platform.

A Realistic Adoption Path for Platform Teams

Governance does not move into the platform all at once. Teams that try to enforce everything immediately usually trigger pushback and rollback. In practice, successful platform teams adopt governance incrementally, using the platform to absorb responsibility step by step.

Step 1: Make implicit rules explicit using stacks and policies

Most organizations already enforce governance informally. Platform engineers know which cloud regions are allowed, which networks are off-limits, and which instance types trigger concern. In Cycloid, this knowledge is first captured directly in stack definitions and policies, not documentation.

Stacks define the approved architecture. Policies define what inputs are allowed. Writing these constraints into the platform exposes where governance currently depends on people reviewing pull requests or tickets instead of systems enforcing rules. This step is diagnostic. Platform teams quickly see which rules are already stable enough to encode and which ones still rely on judgment.

Step 2: Standardize a small number of governed stacks

Rather than covering every use case, platform teams start with one or two stacks that account for most requests. In Cycloid, these stacks encode approved infrastructure patterns, network placement, access boundaries, and cost expectations.

Teams consume these stacks through StackForms, not raw Terraform. Inputs are constrained to what teams are allowed to change. Everything else is fixed by the platform. This immediately removes review work for high-volume paths. Platform engineers stop approving the same Terraform diffs repeatedly because those choices are no longer exposed.

Step 3: Introduce visibility through InfraView before enforcing limits

Before enforcement tightens, teams need shared context. Cycloid’s InfraView exposes ownership, drift, and cost impact across environments in a single view.

Engineers can see what exists, who owns it, and how it behaves over time without needing cloud console access. Platform teams use this visibility to validate that stacks and policies reflect reality before turning enforcement up. Visibility first prevents enforcement from feeling arbitrary. Engineers understand what the platform is protecting because they can see it.

Engineers can see what exists, who owns it, and how it behaves over time without needing cloud console access. Platform teams use this visibility to validate that stacks and policies reflect reality before turning enforcement up. Visibility first prevents enforcement from feeling arbitrary. Engineers understand what the platform is protecting because they can see it.

Step 4: Move routine changes to self-service with enforced validation

Once governed stacks and visibility are in place, routine changes leave the ticket system. Environment creation, scaling within defined limits, and standard updates are requested through StackForms.

Each request is validated automatically against policy before execution. If a request exceeds allowed bounds, it is rejected immediately. No ServiceNow ticket. No manual approval. Platform teams remain involved only when a request genuinely falls outside defined boundaries.

Step 5: Define explicit exception paths without breaking governance

Exceptions still happen. The difference is that they are handled explicitly. In Cycloid, exceptions are tracked as controlled deviations from stacks or policies, not informal one-off approvals.

An exception remains visible, bounded, and auditable. It does not bypass the platform or reintroduce ticket-driven governance. In practice, adoption often starts with one team or one environment class. The platform model is refined, then expanded incrementally. Governance scales because Cycloid absorbs more responsibility over time, not because platform teams review more changes.

Closing Takeaways

By the end of 2025, platform engineering moved from a niche practice to a baseline requirement for large engineering organizations. This was not driven by trend adoption, but by operational pressure. As Red Hat outlines in its analysis on the strategic importance of platform engineering, platforms exist to reduce coordination overhead, standardize delivery paths, and absorb complexity that individual teams cannot manage at scale.

Review-based governance is hitting a throughput ceiling

One pattern became hard to ignore in 2025 i.e., adding more platform engineers stopped improving delivery speed. PlatformEngineering.org’s 2025 predictions describe this clearly. Review queues, approvals, and coordination work became the limiting factor, not infrastructure or tooling. When governance depends on human review, throughput scales with headcount. Most organizations cannot afford that curve going into 2026.

Policy enforcement is moving into execution paths

Another clear shift from 2025 is where governance now lives. Instead of audits and post-deployment checks, teams are enforcing rules directly in pipelines and admission paths. The transition from Infrastructure as Code to Policy as Code is already visible in how enterprises automate governance across CI/CD and infrastructure workflows, as documented in practical write-ups on policy-driven automation in multi-cloud environments. This shift is happening because blocking invalid changes early removes work, while detecting them later creates it.

Platform engineering is spreading beyond early adopters

Platform engineering is no longer limited to hyperscalers or high-growth startups. Community data and industry research show adoption expanding into regulated and mid-sized organizations that need both autonomy and control. PlatformEngineering.org highlights this broadening in its coverage of how the discipline matured through 2025, with increased participation across industries that previously relied on centralized operations teams.

Self-service without enforcement is being rejected

A recurring theme in 2025 discussions was frustration with superficial self-service. UI-driven portals that still rely on approvals failed to reduce load because they preserved the same human bottlenecks. PlatformEngineering.org repeatedly called out this pattern: self-service without enforcement simply relocates the queue.

In 2026, velocity becomes the constraint

Looking into 2026, the pressure point is no longer compliance reporting. It is operational velocity. Teams that treat governance as documentation or after-the-fact reporting will see delivery slow down under manual work. Teams that encode constraints into stacks, policies, and lifecycle workflows will not.

The direction is already visible. Governance that depends on people will continue to consume platform capacity. Governance enforced by systems will not. The difference is not tooling choice. It is whether governance is treated as a human process or a system behavior.

Conclusion

As platforms scale, reviews, approvals, and clarifications accumulate until delivery slows and platform teams become bottlenecks. Platform engineering initiatives that scale governance focus on removing humans from routine decisions. Guardrails become defaults and inputs are constrained. Cost and access boundaries are enforced before resources exist. Visibility replaces guesswork. Exceptions are handled deliberately rather than informally.

When governance is treated as a system behavior rather than a review task, platform teams regain control without adding headcount. This is the operating model behind Cycloid. By replacing ticket-based gates with governance-wrapped self-service, Cycloid allows platform teams to enforce policy constraints automatically, ensuring delivery is fast, predictable, and compliant by design.

FAQs

-

Why does platform governance often become a bottleneck as engineering teams scale?

Governance fails to scale because most organizations treat it as a manual review phase rather than a platform behavior. When rules for security, networking, and budget are enforced by humans reading tickets, the platform team’s workload grows linearly with every new developer or service. This creates a “Ticket-Ops” trap where senior engineers spend more time approving routine requests than building automation.

-

How should we measure the success of platform governance initiatives?

Avoid tracking “ticket volume,” which is a vanity metric. Instead, measure Manual Reviews per Deployment and Change Lead Time. A successful governance initiative should drive manual reviews toward zero for standard stacks while reducing the time it takes to go from “intent” to “provisioned resource.” If lead time remains high, your governance is likely still stuck in approval queues.

-

How can we enforce cloud cost controls without slowing down delivery?

Traditional cost control relies on “GreenOps” reports that flag spending after it happens. To scale, you must move cost governance to the request phase using bounded inputs (StackForms). By encoding monthly budgets and instance-type restrictions directly into the stack definition, the platform automatically rejects over-budget requests before any infrastructure is created, removing the need for finance to review every ticket.

-

What is the difference between a standard Internal Developer Platform (IDP) and a ticketing system?

A ticketing system gathers context and waits for a human to act. A Unified IDP (like Cycloid) validates context and acts immediately. In a ticketing model, governance is a gatekeeper that blocks progress. In a Unified IDP model, governance is a set of pre-approved paths (Golden Paths) that allows self-service to happen safely. The goal is to maximize developer autonomy without sacrificing control.